40 miles east of the town of Kooskia, located in Clearwater National Forest

Kooskia Internment Camp (Department of Justice Internment Camp)

Click on a point on the map or in the sidebar to begin.

A | U.S. Highway 12

U.S. Highway 12 runs parallel to the Lochsa River, through the homelands of the Nimíipuu (Nez Perce). Although the highway was formerly called the Lewis and Clark Highway, the road does not follow the trail that Lewis and Clark traversed. Instead, according to a 1955 Lewiston Tribune report on the road construction, highway engineers chose to follow the river, “literally chiseling a catwalk-like ledge into the face of its granite walls and blasting that into a roadbed.” Thus with loud destruction and nearly violent force, the formerly impassable area was domesticated into a federal highway.

"Road construction sign by road near Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

Construction work began in the 1930s, when a route along the Idaho Forest Highway system was chosen that extended from Kooskia, Idaho to Missoula, Montana. Initially, a project was initiated to use federal prisoners to construct the federal highway. Imprisoned men were assembled from various federal prisons and housed in a camp at Kooskia. The camp was administered and guarded by the Department of Justice while the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) provided all engineering, construction supervision, construction equipment, and operators of all heavy equipment. In the early 1940s, federal prisoners were replaced by incarcerated Issei men. According to an engineer with the BPR beginning in the 1920s, operations on the road building project during WWII “were not greatly different except that the Japanese were less experienced and less adept at construction operations.” The use of prison labor on the road was discontinued after the war, at which point the engineer noted that “even with no common labor costs the unit construction cost was nearly comparable with contractor bid prices for similar work.” In other words, prison labor did not necessarily make the job cheaper.

"Construction project blasting for Highway 12 near Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

The road was completed and dedicated on August 20, 1962. Today, the total distance of the road, from the Washington state line to Montana is 206 miles. The 100-mile stretch of the highway from Kooskia to Montana cost a total of $12.7 million.

At the dedication ceremony of the highway, Wallace C. Burns, chairman of the Idaho Highway Board, said, “Since the days of the first Indian trails, access through this primitive and rugged wilderness has been slowly developed…Now we are new completion of a good, paved highway which finally links the borders of the state to serve modern traffic.”

"Construction equipment in Kooskia drilling into cliff face." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

Today, about 35 miles past the site of the former camp at Kooskia and just east of the town of Kamiah, ID, is a sign for Nez Perce National Historic Site, a non-traditional national park that includes 38 sites spread across the traditional homeland of the nimíipuu (what is now Idaho, Oregon, Montana, and Washington). The Nez Perce National Historic Site between Kooskia and Kamiah is a rest stop and picnic area that features interpretation of one origin story of the nimíipuu, known as tim’né•pe or “Heart of the Monster.” Though only particular sites along US Highway 12 are marked as culturally and historically significant to the nimíipuu, they serve as reminders, for observant travelers, of the ongoingness both of settler colonial processes of removal and of the presence of the nimíipuu today.

Driving along U.S. Highway 12 today, while treacherous in winter months, is truly beautiful. Campgrounds and picnic areas dot the road on both sides, inviting spontaneous stops to admire the river and the view more closely. The stunning beauty of the region seems to hold its past close in view. As we drove up and down Highway 12 in May 2022, the beautiful views raised only more questions for us about the histories of the area, even as the present haunted us in its own ways.

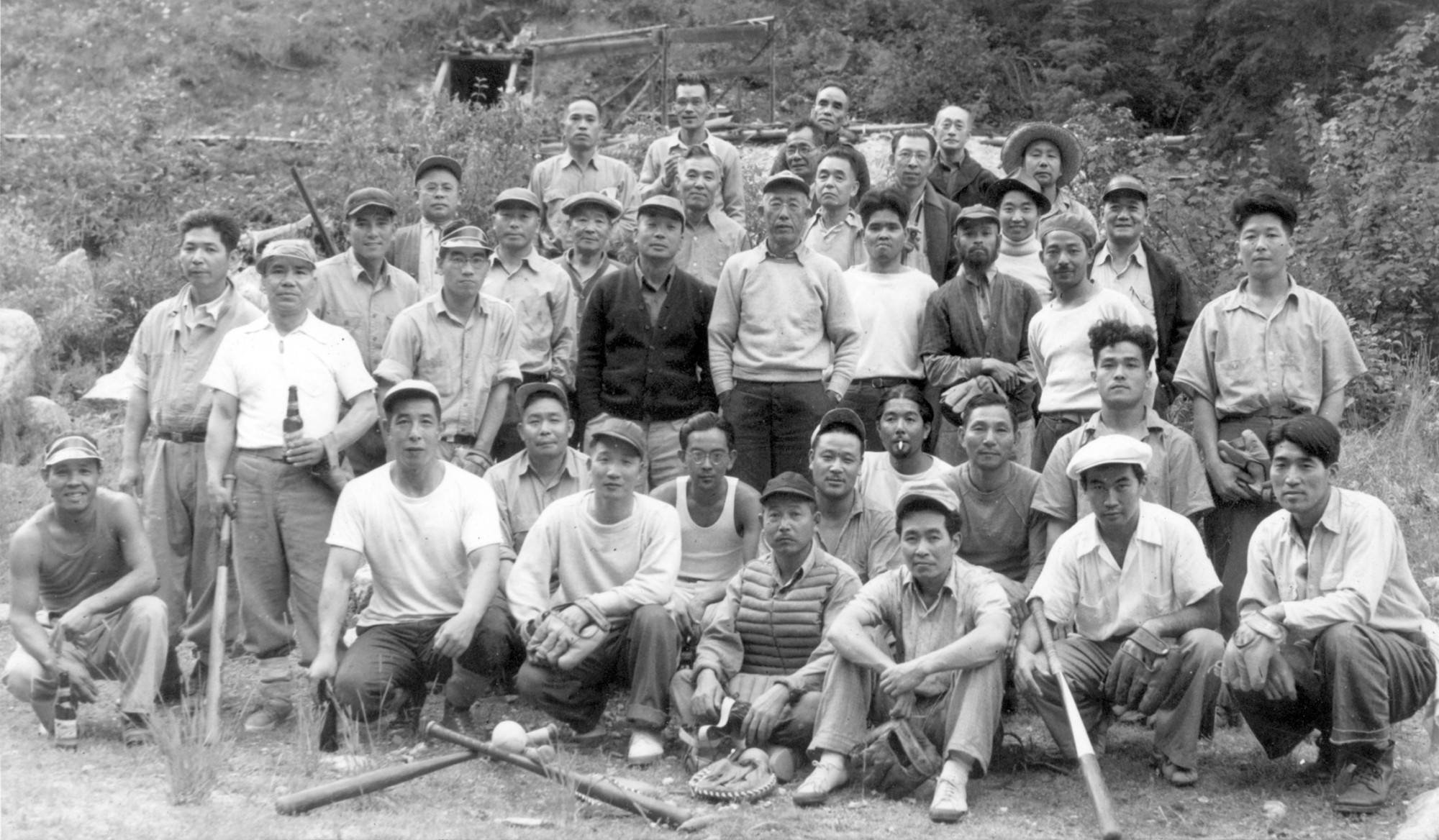

B | Recreation & life (fishing, baseball, and more)

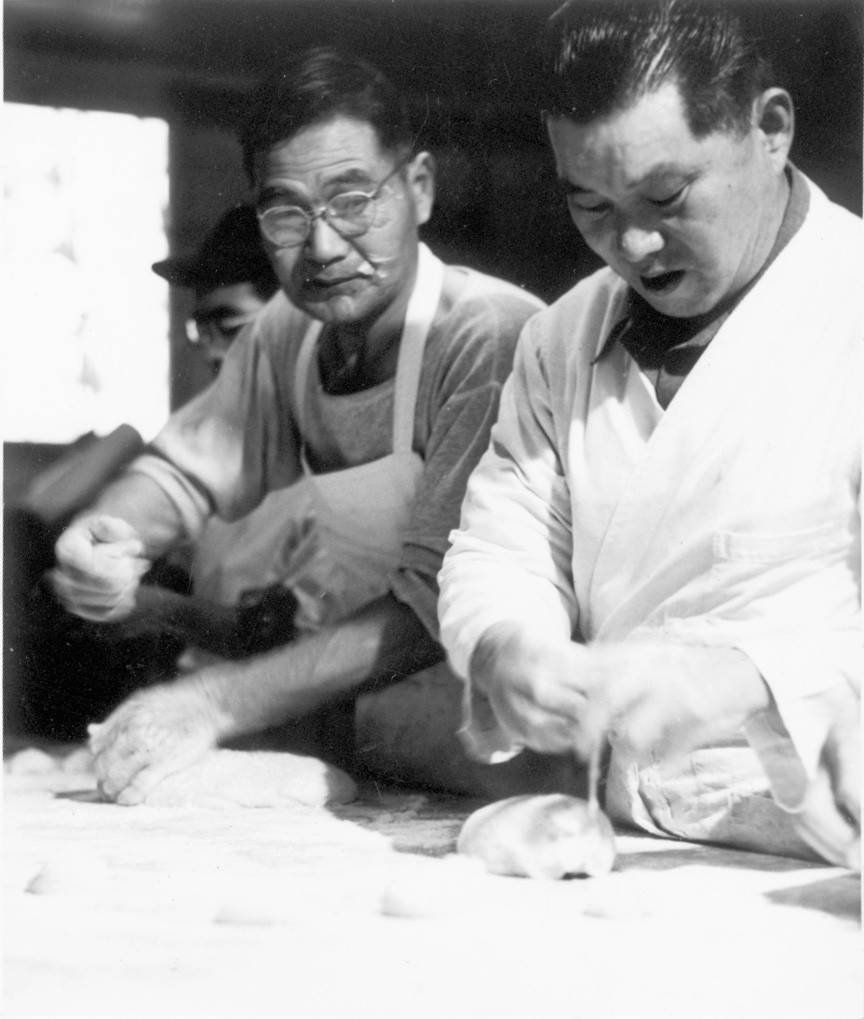

While imprisoned at Kooskia, Issei men created opportunities for recreation like fishing, art, music, baseball, theater performances, and cultural traditions around holidays. The men built an island in the middle of Canyon Creek, which ran through the camp, and would often fish from there. The Lochsa River, which ran along their road building work, is known even today for excellent trout fishing. In part thanks to their knowledge of their rights under the Geneva Convention, the Issei imprisoned at Kooskia insisted on leisure time. In fact, at each of the camps where Japanese were held during World War II, things like baseball games and dances were regular occurrences. While it might surprise you to see that these men, in the midst of war and uncertainty and far from their homes and families, dedicated some of their time to frivolous or fun activities, these were often survival tactics for them, too.

Back left corner of the footage shows the area south of Canyon Creek where the Kooskia baseball diamond was built.

C | Barracks

This footage shows the path along Canyon Creek that would have led to the barracks area when Kooskia Internment Camp was in operation during World War II. Articles 9 and 10 of the Geneva Convention specified that internees were entitled to “the same amount of space as is the standard for United States troops at base camps,” which meant 60 square feet of floor space and enough ceiling height to provide the required 720 cubic feet of air space. The Japanese men at Kooskia seem to have perceived their accommodations there as a significant improvement over lodgings at their previous prisons.

D | Incinerator

One of the last remaining extant structures at the Kooskia site is an incinerator, well-hidden in the woods on the opposite side of Canyon Creek from where the barracks were built while the camp was in operation. Paper garbage was burned in the incinerator while other waste produced at the camp was hauled away to nearby Kooskia town in cans. Sewage flowed into a septic tank under the road.

E | Concrete Slab from the Water Tank

The Kooskia site is heavily wooded and—when we visited in mid-spring—lush with vegetation. After the camp closed, the buildings and other supplies were removed from the site. Today, little remains visibly on the landscape. On our visit to the Kooskia site in May 2021, we searched for evidence of concrete structures or other remains from the camp. Eventually, some digging revealed a large concrete slab buried beneath a light layer of dirt. This concrete slab was likely left from the water tank that served the camp and not, as we initially imagined, a leftover foundation from a barracks building. The water tank was located on a hill above camp and was round and wooden, ten feet in diameter and ten feet high.

F | Lochsa River

The Lochsa River is one of two primary tributaries of the Middle Fork of the Clearwater River. Lochsa means “rough water” in the Nez Perce language. The Salish name for the river means “It Has Salmon.” Before the river became popular for tourists and fishermen, these names suggest that it was a significant part of life for Indigenous peoples in the area. In 1968, the river was included in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. As such, the river has no dams and it is rated as one of the world’s best for continuous whitewater. For many of the Japanese men imprisoned at Kooskia during World War II, the proximity of the river was a bright spot. Priscilla Wegars, in her study of the Kooskia Internment Camp, writes that in early June 1943, one of the officers in charge of Kooskia sought permission for the imprisoned men to fish in the Lochsa River. By July 1944, 48 Japanese internees had purchased fishing licenses (at a cost of $2 per year). The men built boats and rafts for themselves and cooked the fish that they caught.

G | Arrow to administrative Housing

Administrative and other white staff at Kooskia lived in cottages at Apgar Creek, a short distance from the internment camp. At least two employees had children who lived with them during the time they worked at Kooskia. The first superintendent at Kooskia had previously served as an administrator for the federal prison camp at the same site. He transferred to be an INS employee, though he did not remain at Kooskia for long, resigning in late 1943, in part because of his dissatisfaction with the work, especially that he was not able to run the internment camp in the same manner as the prison camp in terms of how the men were treated.

Housing at Kooskia, 1943-1944. Image of housing for staff at Kooskia Internment Camp. PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/, PG 103, Box 1, Scrapbook page 13

Early History

The remains of Kooskia Internment Camp are located on lands that have always been home to the Nimíipu people, called the Nez Perce by early European trappers. To learn more about the history and presents of the Nimíipuu, visit the Nez Perce Tribe’s website.

Today, the portion of Nimíipu land where Kooskia was built is part of the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest in northern Idaho. In the 19th century, after a series of treaties with the U.S. government that gradually stole land from the Nimíipu that resulted in “the Flight of 1877,” where the U.S. Army clashed with Nez Perce, chasing them from their lands. One Nimíipu elder recounted that the events of 1877 can be remembered as “our people’s painful and tragic encounter with ‘Manifest Destiny.’” After 1877, the Nez Perce reservation was reduced to one-tenth of its original size. Even those Nimíipu who had refused to sign the 1863 Treaty, put into place after gold was discovered on Nimíipu land, were evicted from their homelands and moved onto the new reservation

Idaho was admitted to the Union as the 43rd state in 1890. The forest reserves were established by Presidential Proclamation in 1897, becoming the national forest system in 1905. Nez Perce National Forest was defined by the US Forest Service in 1908.

From mid-June to mid-October 1933, the site that would become Kooskia internment camp housed a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp. In late August 1935, the site became a federal prison camp for inmates convicted of federal crimes like mail robbery and selling liquor to Native Americans. The men imprisoned at the Kooskia began construction on what was then called the Lewis-Clark highway, today U.S. Highway 12, between Lewiston, Idaho (near the state border with Washington) and Missoula, Montana.

“Construction at Kooskia Internment Camp." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

According to University of Idaho historian and archaeologist Priscilla Wegars, by early 1943, war expenses meant that appropriations for the prison system were lessened and so the federal prison camp at Kooskia closed. However, because the route had been declared a First Priority Military Highway, the camp reopened almost immediately—with a different form of prison labor.

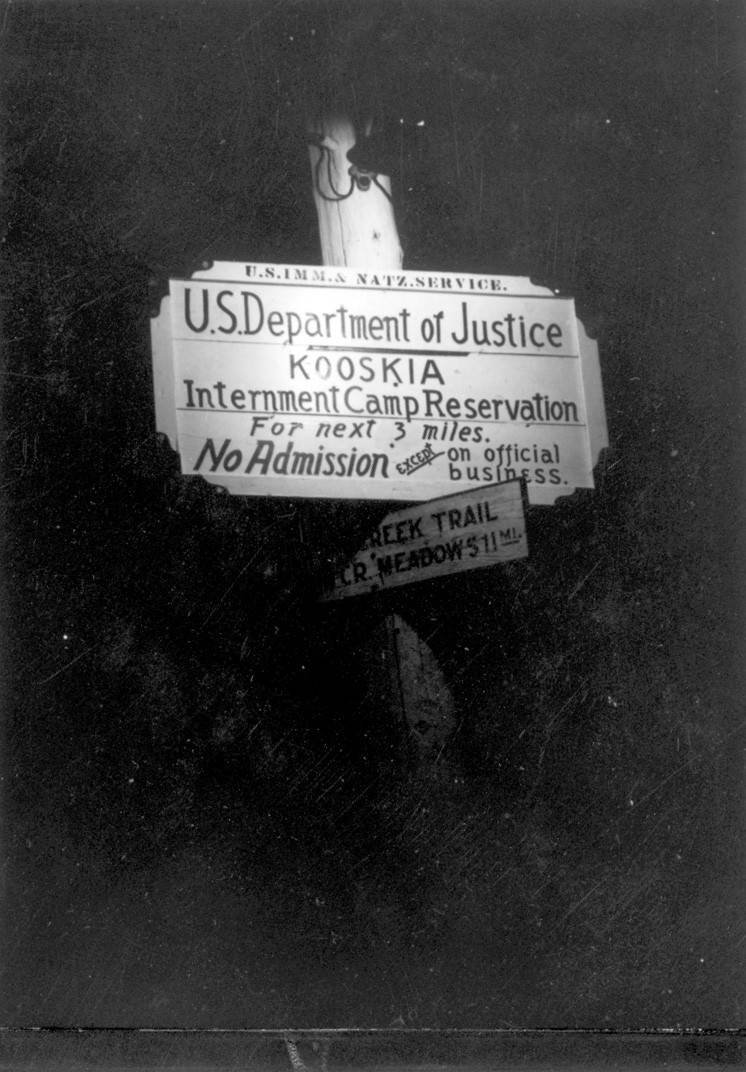

Wartime

"Sign at entrance of camp in Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Meeting in Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

The Kooskia Internment Camp was established in May 1943 about 30 miles east of Kooskia, Idaho in the north central part of the state. The camp was administered by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) for the Department of Justice. For the roughly two years that the camp was in operation, some 265 Issei men were held there, working in the camp and on road construction to build the section of U.S. Highway 12 between Lewiston, Idaho and Missoula, Montana.

Issei held at Kooskia came from 23 U.S. states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Hawai’i, Idaho, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, and Washington) as well as from Latin American countries, chiefly Peru but also Panama and Mexico.

Kooskia was different from other INS-run wartime internment camps in that Issei men could request to be transferred there, in order to earn wages for their labor. Because the camp was administered by the Department of Justice, it was governed under strict accordance with the Geneva Convention.The Issei imprisoned at Kooskia, perhaps because of their experiences at other internment camps, namely Lordsburg in New Mexico, before their arrival at Kooskia, were well-versed in their rights under the Geneva Convention. According to anthropologist Dr. Priscilla Wegars, the men imprisoned at Kooskia were able to achieve a remarkable amount of control over their circumstances, relative to those imprisoned at other wartime detention facilities, because of both their knowledge and use of the Geneva Convention’s provisions and because of their importance to the success of the road building project.

The Kooskia Camp closed on May 2, 1945, with the last remaining 104 Issei sent to the internment camp at Santa Fe. Most of the buildings and materials were quickly removed from the site.

After Incarceration

In 1978, the U.S. Forest Service, who currently owns the property, directed archaeological research at the site and collected ceramic artifacts, including the base of a rice bowl with “MADE IN JAPAN” printed on it. In 2009, the University of Idaho received its first Japanese American Confinement Sites grant from the National Park Service to conduct archaeological testing in the area under the direction of Dr. Stacey Camp.

Today, few structures or remains of the camp are visible at the site, aside from a concrete slab that was likely the base of a handball court and the rough outline of the baseball diamond.

"Working with dough at Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Baseball team for Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Tending flowers at Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Making mochi in an usu at Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Men playing instruments at Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Man fishing near Kooskia Internment Camp." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Performance in traditional costume at Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Buildings at Kooskia showing Canyon Creek and road." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

"Fishing equipment and antlers in Kooskia." Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, PG 103, Kooskia Internment Camp Scrapbook, University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives, http://www.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/.

Works Cited

For more general information, see our resources page.